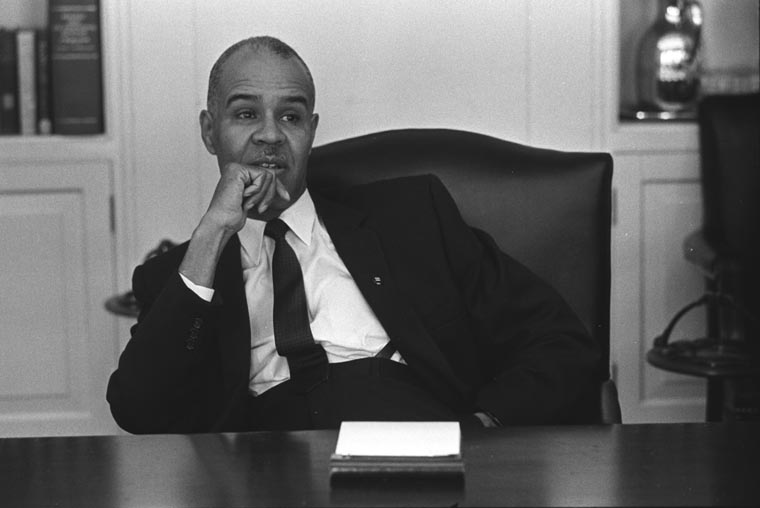

Roy Wilkins was born on August 30, 1901, in St. Louis, Missouri. After his mother died when he was just 4 years old, he and his siblings went to live with his maternal aunt and her spouse in the region of St. Paul, Minnesota. He majored in sociology and journalism at the University of Minnesota, working various jobs to support his way—including as an editor for the university newspaper and the African-American periodical The St. Paul Appeal. Wilkins graduated from the school in 1923. He wed social worker Aminda “Minnie” Badeau in 1929.

Upon his move to Kansas City, taking an editorial position with the Kansas City Call in 1923, Wilkins was confronted with the viciousness of Jim Crow laws. He engaged in staunch activist work, eyeing politicians who were known for their overt racism, and eventually moved to New York in 1931 to serve as assistant to Walter White, head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Working with the group’s strong anti-lynching efforts, Wilkins also went undercover to observe and take part in the horrible job conditions African Americans toiled under as part of a federally funded river initiative in Mississippi. Wilkins’s ensuing Mississippi Slave Labor report was instrumental in producing change for the workers.

By the mid-1930s, Wilkins had succeed intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois as editor of the NAACP’s Crisis magazine, which Wilkins ran for a decade and a half. Later on, he was one of the key players in getting the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case to the Supreme Court, whose ruling declared public school segregation illegal. With White’s passing in 1955, Wilkins was voted in as the NAACP’s executive secretary, later known as executive director. Wilkins continued his work as a pivotal figure in the Civil Rights Movement. He believed in achieving social equality through legislation and Constitutional backing, and during speeches, urged African Americans to embrace U.S. citizenship. He went on to become an advocate of black-owned bank lending power and met with various U.S. presidents, including John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, to advocate on his constituency’s behalf.

Wilkins was also an instrumental figure in Congress’ passing of the Civil Rights Acts of the 1950s and ’60s, and was one of the key leaders in organizing the historic March on Washington, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. shared his “I Have a Dream” speech. Additionally, Wilkins helped to oversee a rise in NAACP membership from 25,000 members in the 1930s to more than 400,000 by the 1970s. During the late ’60s, Wilkins was wary of the more militant Black Power Movement, and was accused by some of having too conciliatory a tone. After being asked to step down by some within the organization and initially refusing, he retired from the NAACP in 1977, with Benjamin Hooks taking over leadership.

Wilkins died on September 8, 1981, in New York City, due to kidney failure and heart issues. He received many awards and honors during his lifetime; books on him include his 1982 posthumously published autobiography, Standing Fast, as well as 2005’s Roy Wilkins: Leader of the NAACP by Calvin Craig Miller. Wilkins’s alma mater, the University of Minnesota, created the Roy Wilkins Center for Human Relations and Human Justice.